Basics of Functions¶

Overview, Objectives, and Key Terms¶

With some simple programs under our belts, it is time to modularize our programs by using functions. In this lecture and Lecture 13, you will learn how to define your own functions to meet a variety of needs.

Objectives¶

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to

- Define a function that accepts (zero or more) input arguments and returns (zero or more) values.

- Explain the meaning of a named and default argument.

- Use unpacking to define multiple variable in a single statement.

- Include functions in flowcharts.

Key Terms¶

- function

def- call

- argument

- return value

- unpacking

- named (or keyword) argument

- default value

What is a Function?¶

For our purposes, a function is something that is executed (possibly

with input) and provides some sort of output. Often, this output will be

a value (or several values) explicitly returned by the function.

However, functions can also be used to modify the very data given to

them as input. Although you’ve been using functions all along (e.g.,

those provided by the math module like math.cos), you’ll understand

how to define and use your own functions by the end of this lesson.

Let’s start by example. Consider the sum of an array \(x\), defined mathematically as \(s = \sum^n_{i=1} x_i\) and computed in Python via

In [1]:

x = [1, 3, 4, 2, 4]

s = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

s += x[i]

This short program is specific to the value of x defined. If it were

to be applied for any value of x, it must first be turned into a

function. Functions, like conditional statements and loops, are defined

in Python using a special keyword. The basic structure is as follows:

def function_name(arg1, arg2, ...):

# do something to define rval1

# do something else to define rval2

# and so on...

return rval1, rval2, ...

Following the def keyword is the name of the function and a pair of

parentheses. Inside these parentheses are the names of zero or more

input arguments. Each argument name (e.g., arg1) can be used

within the function like normal variables. After all computations are

performed, the function can include a return statement with zero or

more return values (e.g., rval1). As observed for if,

while, and for statements, the block of code following the

def line must be indented.

Let’s adapt the structure shown above to the summation problem. The

input required is the sequence of numbers x, and the output is the

sum of x. Hence, we need one input argument and one return

value:

In [2]:

def compute_sum(x):

s = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

s += x[i]

return s

Now, just like the other functions we’ve used (e.g.,``math.cos``), the

function compute_sum can be called repeatedly with different

arguments:

In [3]:

compute_sum([1, 2, 3, 4])

Out[3]:

10

In [4]:

compute_sum([100, 200, 300])

Out[4]:

600

Even though the initial x was a list, the input to compute_sum

need not be a list: it just has to support indexing via [] and have

values that are numbers.

Exercise: See what happens when

(1, 2, 3)andnp.linspace(0, 10)are given tocompute_sum.Exercise: Write a function named

factorialthat computes \(n!\).Exercise: Write a function that determines whether a positive integer

nis prime. A prime number is any number divisible only by one and itself. By definition, one is not considered prime. The function should returnTrueorFalse.Exercise: Write a function with no arguments and no return values that prints out the day of the week. Hint: look up the module

datetime.

One potential pitfall when defining functions is to forget to return a

value. Consider this alternative (and wrong) version of the summation

function and how it can lead to unexpected TypeError errors:

In [5]:

def compute_sum_wrong(x):

s = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

s += x[i]

In [6]:

# define a sum

s = compute_sum_wrong([1, 2, 3])

# and then double it

s *= 2

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-6-1781b50e1daf> in <module>()

2 s = compute_sum_wrong([1, 2, 3])

3 # and then double it

----> 4 s *= 2

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for *=: 'NoneType' and 'int'

The problem appears to be the statement s *= 2, but s should be

an int value, right? Nope:

In [7]:

type(s)

Out[7]:

NoneType

Any function without explicit return values returns None.

Warning: Be sure to check that functions return any values expected when called.

Functions with Multiple Return Values¶

In some applications, programs can be simplified by using functions with

multiple return values. For example, consider the problem of computing

the mean and standard deviation of an array \(x\) with \(n\)

elements. Recall, the mean of \(x\) is

\(\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n} \sum^n_{i=1} x_i\), while the variance is

defined by \(\mu = \frac{1}{n}\sum^n_{i=1} (x_i -\bar{x})^2\).

Surely, one could implement two separate functions (like np.mean and

np.var), but they can be combined in one function:

In [8]:

def mean_and_var(x):

mu = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

mu += x[i]

mu /= len(x)

var = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

var += (x[i] - mu)**2

var /= len(x)

return mu, var

Now, calling this function with x = [1, 2, 3] leads to

In [9]:

vals = mean_and_var([1, 2, 3])

vals

Out[9]:

(2.0, 0.6666666666666666)

The output (here, vals) is a tuple. Actually, this is expected:

the statement return mu, var is equivalent to return (mu, var).

With vals defined, one could set mu = vals[0] and

var = vals[1], but it is simpler to use

In [10]:

mu, val = mean_and_var([1, 2, 3])

print(mu, val)

2.0 0.6666666666666666

In fact, this shows a neat feature of Python: the elements of a

tuple (or list) can be assigned to several names all at once

using a process called unpacking. This feature of Python can yield

very compact, multiple assignments and lets one swap two values with one

statement. For example:

In [11]:

a, b = (1, 2) # a and b from tuple

print(a, b)

a, b = [2, 1] # a and b from list

print(a, b)

c, d = b, a # c and d from b and a

print(c, d)

c, d = d, c # swap c and d

print(c, d)

1 2

2 1

1 2

2 1

Just as one must be careful to ensure the correct values are returned by a function, one must also be sure to capture that output correctly. If, for example, a function returns three values, then one cannot set two values equal to that function’s output, e.g.,

In [12]:

def return_three():

return 1, 2, 3

a, b = return_three()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-12-a4eb1b5d0866> in <module>()

1 def return_three():

2 return 1, 2, 3

----> 3 a, b = return_three()

ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2)

Again, a ValueError pops up, now because we attempted to unpack

three return values into two variables.

Functions with Multiple Arguments¶

Functions like plt.plot and np.dot naturally accept two (or

more) input arguments to produce a particular output (be it a

visualization or the dot product of two arrays). There is no limit to

the number of arguments a Python function can accept. Furthermore, some

arguments can be made optional by providing default values.

Consider the following function foo, which accepts three input

arguments x, y, and z, and prints them in a particular

format:

In [13]:

def foo(x, y, z) :

print("(x, y, z) = ({:.4f}, {:.4f}, {:.4f})".format(x, y, z))

As defined, one must pass three values to foo for x, y,

and z, e.g.,

In [14]:

foo(1, 2, 3)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

However, suppose y and z represent values that do not often

change. That is, perhaps there are good default values that can be

assigned to y and z for most applications. Here, assume those

values are y = 1.1 and z = 2.2. A new version of foo may

then be defined with these default values:

In [15]:

def foo_with_defaults(x, y = 1.1, z = 2.2):

print("(x, y, z) = ({:.4f}, {:.4f}, {:.4f})".format(x, y, z))

This new function can be called just like the original version, i.e., with all three input arguments defined:

In [16]:

foo_with_defaults(1, 2, 3)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

However, with defaults defined for y and z,

foo_with_defaults can also be called in the following ways:

In [17]:

foo_with_defaults(1, 3) # let z be its default value

foo_with_defaults(1) # let y and z be their default values

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 3.0000, 2.2000)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 1.1000, 2.2000)

The result of the first call shows that y is 3. In other words,

the arguments passed are assigned to the names in the order they appear

in the function definition. Passing just one value (the second call)

leads to default values for both y and z.

Now, what if we wanted to pass a value for z but are fine with the

default value for y? In Python, that’s easy, just name the

argument z when calling foo:

In [18]:

foo_with_defaults(1, z=3) # y is still defaulted to 1.1

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 1.1000, 3.0000)

In fact, arguments can always be named explicitly:

In [19]:

foo_with_defaults(x=1, y=2, z=3)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

However, once an argument has been named, all subsequent arguments must also be named. For example, the following fails:

In [20]:

foo_with_defaults(1, y=2, 3)

File "<ipython-input-20-2c7ebed8818b>", line 1

foo_with_defaults(1, y=2, 3)

^

SyntaxError: positional argument follows keyword argument

This particular SyntaxError points out that arguments can be

positional or keyword arguments. Any variable we name explicitly

is a keyword argument. We’ll learn more about these terms in

Lecture 13.

With named arguments, one can pass arguments in any order. For example,

consider the following three calls of foo_with_defaults:

In [21]:

foo_with_defaults(1, z=3, y=2)

foo_with_defaults(z=3, y=2, x=1)

foo_with_defaults(y=2, x=1, z=3)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

(x, y, z) = (1.0000, 2.0000, 3.0000)

Each call yields exactly the same output.

Function Documentation¶

From the very beginning, the use of internal documentation via help

has been emphasized. The value of help, however, depends on

developers to provide the information displayed. That responsibility now

turns to you, the function writer.

Suppose you’ve provided your friend the compute_sum function, and

she did was not quite sure how to use it. If she read Lecture

1, she might try

In [22]:

help(compute_sum)

Help on function compute_sum in module __main__:

compute_sum(x)

Well, that output is not very helpful. What compute_sum is missing

is a docstring. A

docstring is a string placed immediately below the first line of a

function (i.e., after the def function_name(arg1, ...): line.

Ideally, this string says something about the function, including how to

use it and what it does.

For compute_sum, one possible docstring is

"""Returns the sum of an array x.""". Inserting this string below

the def line of compute_sum leads to the following, documented

function:

In [23]:

def compute_sum_with_docstring(x):

"""Returns the sum of an array x."""

s = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

s += x[i]

return s

In [24]:

help(compute_sum_with_docstring)

Help on function compute_sum_with_docstring in module __main__:

compute_sum_with_docstring(x)

Returns the sum of an array x.

More complicated functions require more detailed documentation, and with

the triple, double-quote strings, multi-line docstring values are

possible. A version of compute_sum with more detailed documentation

is the following:

In [25]:

def compute_sum_with_verbose_docstring(x):

"""Returns the sum of an array x.

Inputs

x: sequential type with numerical elements

Returns

s: the sum of the elements of x

"""

s = 0

for i in range(len(x)):

s += x[i]

return s

In [26]:

help(compute_sum_with_verbose_docstring)

Help on function compute_sum_with_verbose_docstring in module __main__:

compute_sum_with_verbose_docstring(x)

Returns the sum of an array x.

Inputs

x: sequential type with numerical elements

Returns

s: the sum of the elements of x

Now your friend has all she needs to use the function!

Note: Always provide a docstring for functions you define.

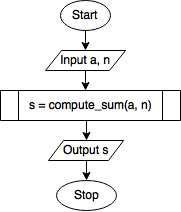

Functions and Flowcharts¶

Fundamentally, functions do not add anything new to our basic logical

structures. Functions can perform computations involving sequences,

selection (if), and iteration (while or for), just like our

programs have done up to this point. The difference in practice is that

a function lets one define such operations once and use them repeatedly

within a program without writing the same lines of code repeatedly.

Ultimately, substituting a function name in place of a large chunk of

code can improve readability and one’s ability to debug the program.

Pseudocode is flexible, and function calls can be described pretty

directly (e.g., Set s to the sum of array a). To include functions

in flowcharts requres a new shape. Before, a simple rectangle had been

used to define processes (usually, single statements like

i = i + 1). Another rectangle, with double vertical bars, can be

used to represent functions, as in the following figure:

Program to compute sum that uses the compute_sum function.

Surely, this flowchart is simpler than it would be were the function not

used. When developing flowcharts for programs that use functions, it is

recommended that separate flow charts are provided for those functions

that you wrote. For others, you may not know enough about the particular

implementation to create the flowchart. For example, np.sum isn’t as

easy as you would think!

Further Reading¶

None at this time.